Earlier today I was on a panel at Hinshaw & Culbertson’s LMRM Conference in Chicago. This was the 23rd annual LMRM Conference, and the event has become the gold standard for events that focus on the “law of lawyering.”

Our session was titled How Soon is Now—Generative AI, How It Works, How to Use it Now, How to Use it Ethically. Preparing for and participating in the event gave me the opportunity to seriously consider some of the key issues relating to how lawyers are using generative AI and the promise that wider future adoption of these technologies in the legal industry holds.

Here are a few key takeaways:

-

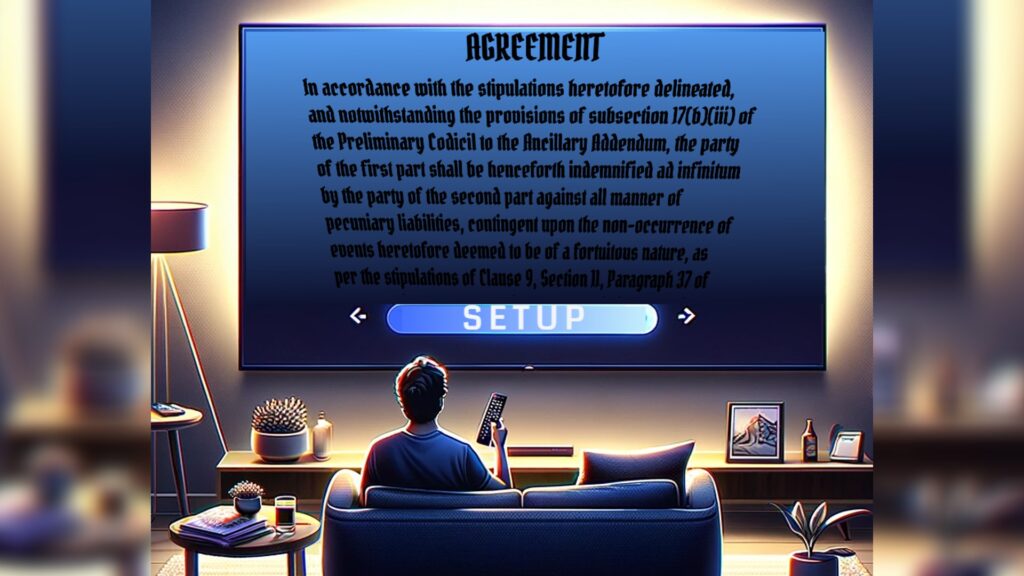

- Effective use. Lawyers are already using generative AI in ways that aid efficiency. The technology can summarize complex texts during legal research, allowing the attorney to quickly assess if the content addresses her specific interests, is factually relevant, and aligns with desired legal outcomes. With a carefully crafted and detailed prompt, an attorney can generate a pretty good first draft of many types of correspondence (e.g., cease and desist letters). Tools such as ChatGPT can aid in brainstorming by generating a variety of ideas on a given topic, helping lawyers consider possible outcomes in a situation.

-

- Access to justice. It is not clear how generative AI adoption will affect access to justice. While it is possible that something like “legal chatbots” could bring formerly unavailable legal help to parties without sufficient resources to hire expensive lawyers, the building and adoption of sophisticated tools by the most elite firms will come at a cost that is passed on to clients, making premium services even more expensive, thereby increasing the divide that already exists.

-

- Confidentiality and privacy. Care must be taken to reduce the risk of unauthorized disclosure of information when law firms adopt generative AI tools. Data privacy concerns arise regardless of the industry in which generative AI is used. But lawyers have the additional obligation to preserve their clients’ confidential information in accordance with the rules governing the attorney-client relationship. This duty of confidentiality complicates the ways in which a law firm’s “enterprise knowledge” can be used to train a large language model. And lawyers must consider whether and how to let their clients know that the client’s information may be used to train the model.

-

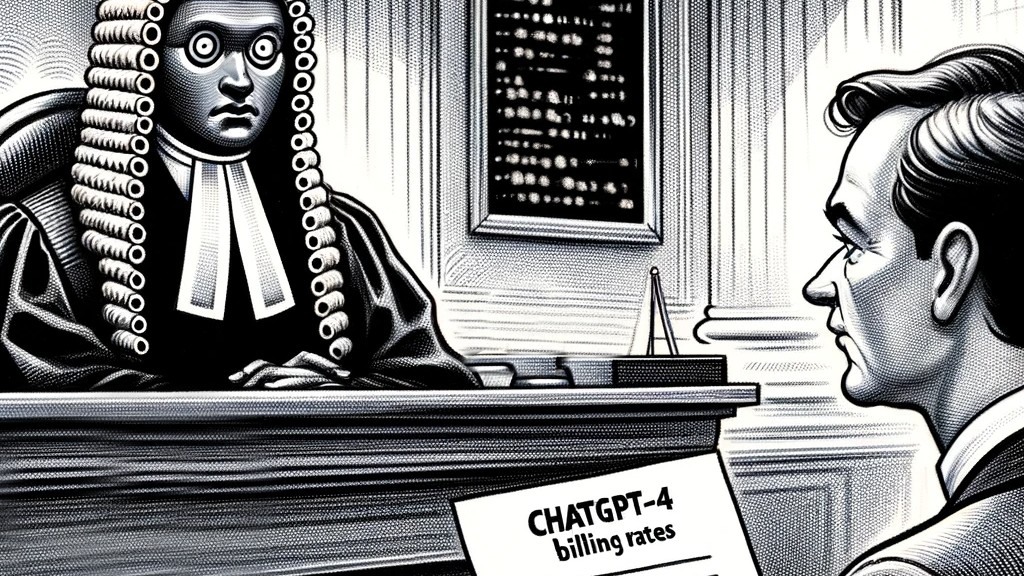

- Exposing lawyering problems. Cases such as Mata v. Avianca, Park v. Kim and Kruse v. Karlen—wherein lawyers or litigants used AI to generate documents submitted to the court containing non-existent case citations (hallucinations)—tend to be used to critique these kinds of tools and tend to discourage lawyers from adopting them. But if one looks at these cases carefully, it is apparent that the problem is not so much with the technology, but instead with lawyering that lacks the appropriate competence and diligence.

- AI and the standard of the practice. There is plenty of data suggesting that most knowledge work jobs will be drastically impacted by the use of AI in the near term. Regardless of whether a lawyer or law firm wants to adopt generative AI in the practice of law, attorneys will not be able to avoid knowing how the use of AI will change norms and expectations, because clients will be effectively using these technologies and innovating in the space.

Thank you to Barry MacEntee for inviting me to be on his panel. Barry, you did an exemplary job of preparation and execution, which is exactly how you roll. Great to meet my co-panelist Andrew Sutton. Andrew, your insights and commentary on both the legal and technical aspects of the use of AI in the practice of law were terrific.